School Segregation is a Teacher Issue

Teachers unions can help save public education by fighting for integration

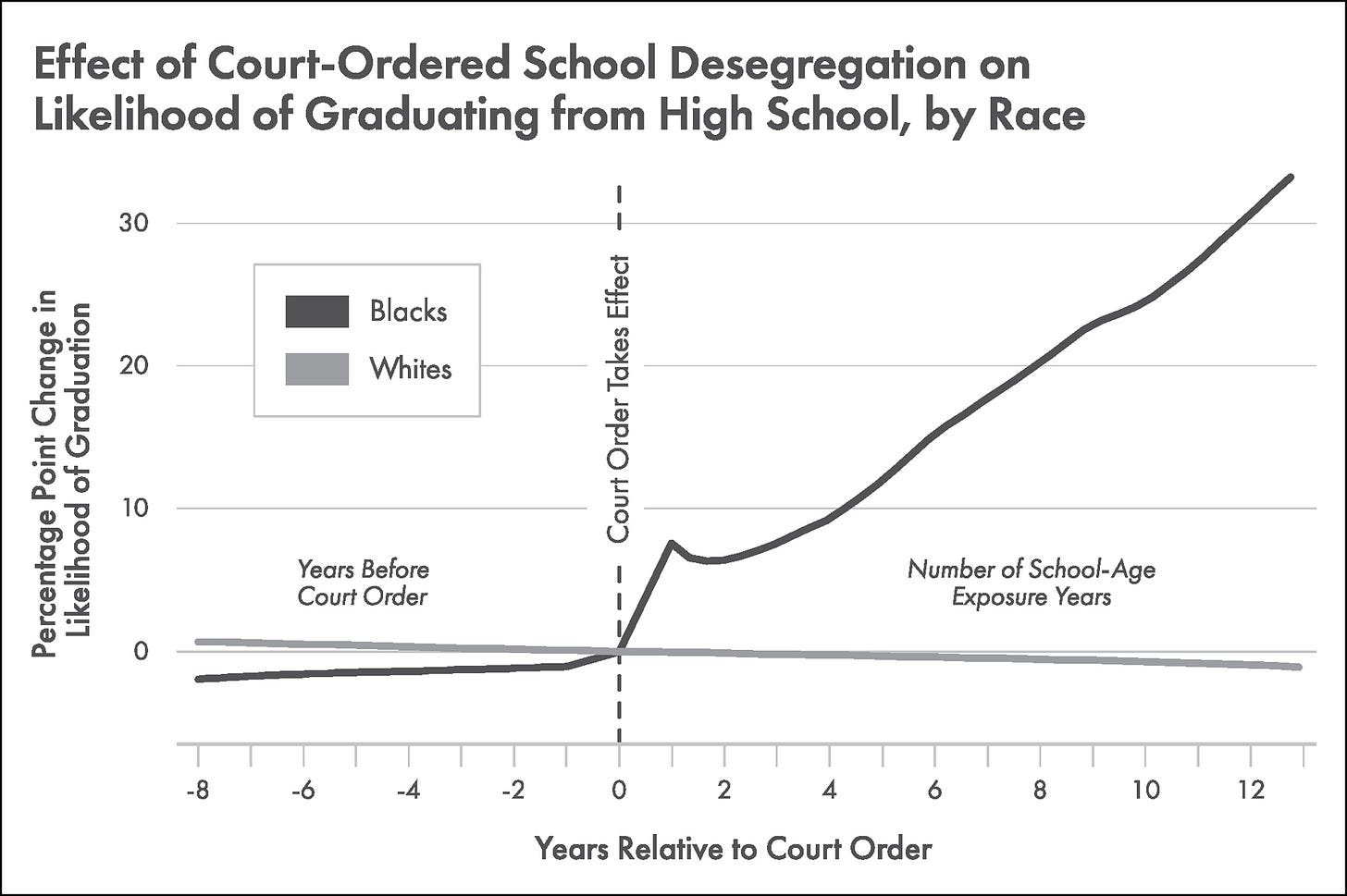

Students and teachers alike have a lot to gain from school integration. Recent scholarship by economist Rucker C. Johnson, author of Children of the Dream: Why School Integration Works (2019), shows that a Black students’ exposure to court-ordered integration correlated with higher grades and graduation rates, higher wages, and lower incidence of crime—with no statistical negative impact on white students. Why? When integration is mandated pro-education reforms tend to come in a package, and these gains persevere as they create a powerful group of stakeholders invested in their protection against political resistance. Johnson shows that integration lowered class sizes and increased school funding. It’s reasonable to expect that, somewhere along the chain of causality, better learning conditions also improved working conditions such that teacher retention increased and, therefore, students started learning from more experienced and better resourced teachers. Working and learning conditions indeed go hand-in-hand.

The flip side of this coin is that students and teachers have lost a lot to school segregation. Noliwe Rooks, author of Cutting School: The Segrenomics of American Education (2016), shows that an industry has developed that profits enormously from school segregation. This industry—including testing, technology, and curriculum companies, charter schools, consulting firms—pockets government money earmarked for poor students of color by selling products it markets as special solutions to the racial achievement gap. Of course, these products are really gimmicks and fake substitutes for what Rooks and Johnson show actually improves educational outcomes—integration (and its effects). Furthermore, the same industry that usurps money meant to improve Black and brown education as the Civil Rights Movement intended; that in its quest for profit innovates endless gimmicks that superintendents and principals force on us, always without support or training, every few years; this same industry uses its government-funded power to beef up the corporate ed reform movement’s attack on teachers. When NYC Mayor Adams and (now former) Chancellor Banks act against their legal obligation to lower class size and defend exclusionary admissions policies, they’re cultivating a market for the school segregation industrial complex whose electoral support they count on. Why should teachers allow this predatory, anti-union behavior to continue?

Students and teachers have a common enemy in what Rooks has termed “segrenomics.” But for decades teachers unions have played into their school boards’ attempts to divide teachers from families, with the boards often invoking race as a wedge (a common tactic used by bosses in the history of the U.S. labor movement). NYC may be the most extreme example of this historically. Here, the civil rights movement developed concurrently with the teachers rights movement. The Teachers Union (TU) is often remembered by activists today as the “anti-racist” group, but the Teachers Guild (TG, a predecessor to the UFT) was also involved in civil rights efforts led by its Black members such as Layle Lane and Richard Parrish. Unfortunately, TU members were unable to grow their base and lead on other issues that concerned most of their coworkers, and were unable to grow enough to withstand the red scare. The TG and later the UFT were very much able to tap into widely felt issues, but in a way that increasingly redefined teachers rights as protections needed from their students and their families, undermining their civil rights work as they embraced stereotypes about families of color.

There’s a longer story to tell here that perhaps I’ll tell another time. But suffice it to say that, the Board of Education got away with failing to integrate the school system by blaming teachers for the system’s woes. As civil rights groups amplified demands for justice—such as consequences for verbally and physically abusive teachers, the transfer of experienced teachers to schools staffed mostly with inexperienced, unlicensed, and substitute teachers, and say over the curriculum their children were taught—the UFT responded unsympathetically, demanding for itself the right to remove what it called “disruptive” children, the right to teach without the threat of transfer to a “bad” school (affirming to families of color that white teachers saw them as inferior), and the right to teach without interference from families who may have been concerned about the representation of their community in the curriculum. The Board successfully goaded the UFT into attacking rather than making common cause with the local civil rights movement. Instead of conflict resolution and coalition building, UFT bureaucrats capitalized on the white panic spreading throughout the country in the 60s and used it to augment their power. The long-term beneficiary of this divide-and-conquer moment was an industry that hates teachers and gets rich from students who are divided by their classrooms’ apartheid walls. Will we be played again?

Today the UFT has an opportunity to lead in NYC’s school desegregation movement. It can create a Civil Rights or Integration Committee—an idea I suggested at an Executive Board meeting two years ago—tasked with organizing education for union members, forming and deepening collaboration with family and student groups, and developing strategy for winning reforms and defeating rollbacks. Some may say that our union is too divided to have a position on integration policies, but this is more reason to host debate and find consensus around an issue that has historically upset our working conditions as well as our union’s reputation among teachers and communities of color alike. If we stand passively on the sidelines, we risk the blame for problems in education manufactured by policymakers and their rich backers. Instead, the UFT can become the crucial force that the school integration movement has always needed.