Dr. King, the UFT, and the Role of Labor

The best way to honor Dr. King’s legacy is to embrace his radicalism, his emphasis on solidarity, and his tactics of civil disobedience and mass action

Fortunately, knowledge of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s long-standing commitment to economic justice is becoming widespread. His preoccupation with the labor movement is well documented in historian Michael K. Honey’s fantastic book, To the Promised Land. For example, in 1964 before the Selma campaign, Dr. King joined the picket line of striking workers—mostly Black women—at a Scripto pen and pencil factory employed in Atlanta. In 1966, his organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), called for the repeal of Taft-Hartley, knowing well that this 1947 anti-labor law had enhanced Jim Crow throughout the South. From Honey’s book we learn how labor permeated Dr. King’s thoughts and actions throughout his life. We read that Dr. King worked briefly in a southern factory as a teen before quitting after the foreman called him a nigger. We also learn that he worked one summer on a tobacco farm in the North, where he realized “that the poor white was exploited just as much as the Negro.”

The older Dr. King, in a 1961 speech to the AFL-CIO, made it clear that anti-labor forces are a threat to the Civil Rights Movement with which he is most associated today:

"In our glorious fight for civil rights, we must guard against being fooled by false slogans, such as ‘right to work.’ It is a law to rob us of our civil rights and job rights. Its purpose is to destroy labor unions and the freedom of collective bargaining by which unions have improved wages and working conditions of everyone…Wherever these laws have been passed, wages are lower, job opportunities are fewer and there are no civil rights."

Indeed, the connection between civil rights and labor is evident insofar as they have a common enemy, which makes the activity of Black workers strategically important to the labor movement:

Our needs are identical with labor's needs — decent wages, fair working conditions, livable housing, old age security, health and welfare measures, conditions in which families can grow, have education for their children and respect in the community. That is why Negroes support labor's demands and fight laws which curb labor. That is why the labor-hater and labor-baiter is virtually always a twin-headed creature spewing anti-Negro epithets from one mouth and anti-labor propaganda from the other mouth.

In fact, to conceive of civil rights and labor rights as separate issues—thus of Black people on one side and the working class on the other—is itself a construct historically manufactured against both:

Together we can bring about the day when there will be no separate identification of Negroes and labor. There is no intrinsic difference as I have tried to demonstrate. Differences have been contrived by outsiders who seek to impose disunity by dividing brothers because the color of their skin has a different shade. I Look forward confidently to the day when all who work for a living will be one with no thought to their separateness as Negroes, Jews, Italians or any other distinctions.

However, although the interests of Black people and the labor movement are one and the same, this does not mean that issues around race should be deprioritized over narrow economic ones. For example, in his speech, Dr. King challenged the AFL-CIO to take action against racism in its own unions:

Labor should accept the logic of its special position with respect to Negroes and the struggle for equality. Although organized labor has taken actions to eliminate discrimination in its ranks, the standard for the general community, your conduct should and can set an example for others, as you have done in other crusades for social justice. You should root out vigorously every manifestation of discrimination so that some internationals, central labor bodies or locals may not besmirch the positive accomplishments of labor.

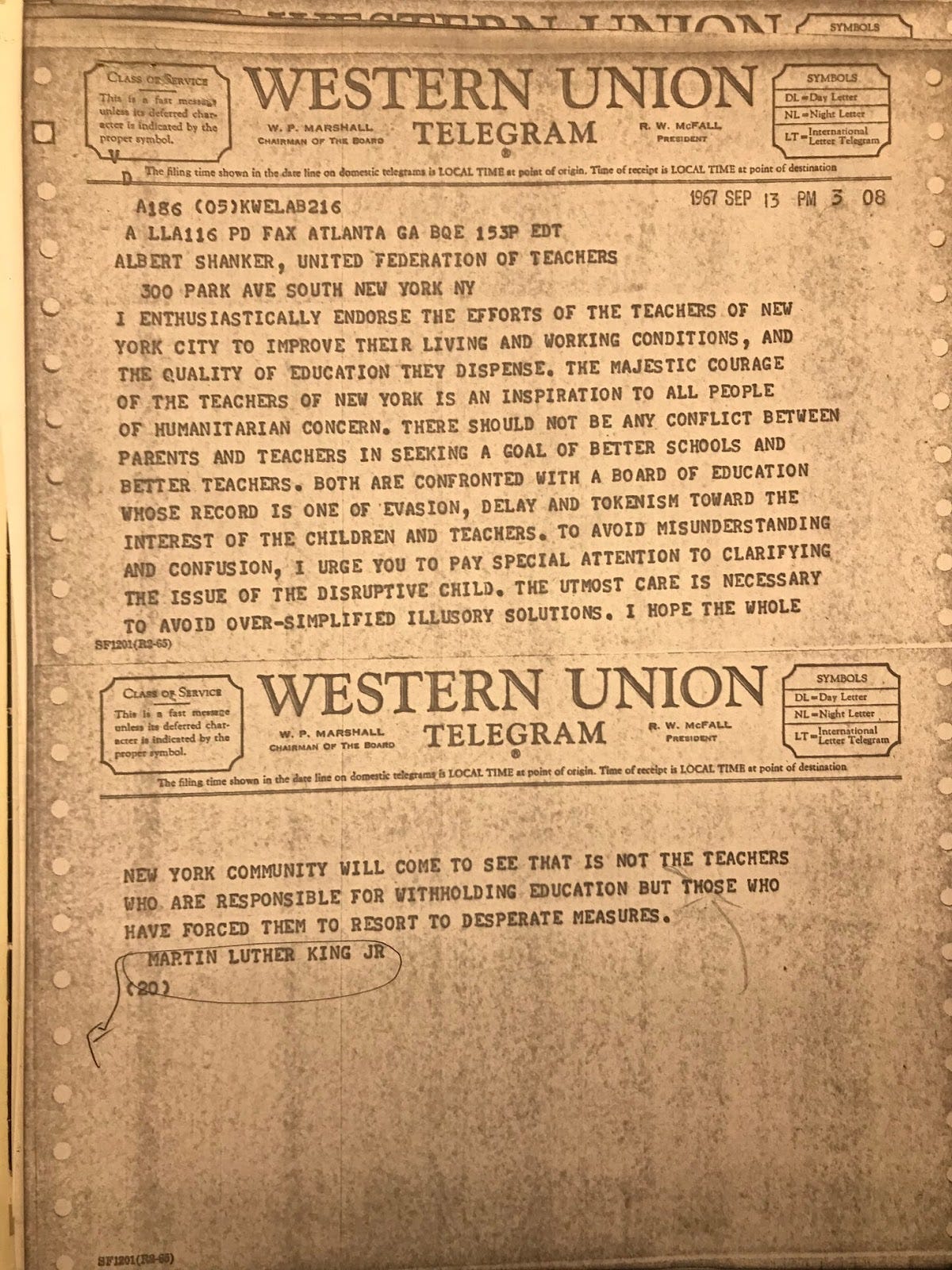

Six years later, Dr. King would repeat a similar point on racial discrimination. In 1967, my union the United Federation of Teachers (UFT) went on strike over school funding and, crucially, over a “disruptive child” clause that it wanted in the contract. This clause would’ve allowed teachers to more easily remove students from their classrooms. UFT president Albert Shanker claimed this would improve his members’ working conditions. The provision, however, was criticized by the African-American Teachers Association (ATA) for granting police powers to white teachers to remove Black students. Members of ATA would eventually resign from the union over the UFT’s support for the clause. When I went through the archives at NYU a few years back, I found this telegram from Dr. King to Albert Shanker where he extended his support for the strike. He ends the telegram, however, with some feedback on the disruptive child clause:

To avoid misunderstanding and confusion, I urge you to pay special attention to clarifying the issue of the disruptive child. The utmost care is necessary to avoid over-simplified illusory solutions.

Earlier in 1967, Dr. King gave his landmark speech at Riverside Church against the war in Vietnam. Against the advice of his colleagues, he explained publicly how the Democrats’ war on the Vietnamese amounted to an attack on the working class at home:

Despite feeble protestations to the contrary, the promises of the Great Society have been shot down on the battlefield of Viet Nam. The pursuit of this widened war has narrowed domestic welfare programs, making the poor, white and Negro, bear the heaviest burdens both at the front and at home...

In November that year, Dr. King would put labor on notice. He knew the labor movement had the power to stop the Vietnam War, but unfortunately in the anti-war movement: "one voice was missing. The loud clear voice of labor.” The consequence of labor’s absence was giving the right an opening: “The war has strengthened domestic reaction. It has given the extreme right, the anti-labor, anti-Negro, and anti-humanistic forces a weapon of spurious patriotism to galvanize its supporters into reaching for power, right up to the White House.” The UFT’s absence was especially glaring, as the union had prided itself as a socially conscious union; however, it had been becoming increasingly reactionary as it entrenched itself into a right-moving Democratic party.

For making his anti-war ideas public, Dr. King was condemned by liberal elites and other civil rights leaders. His own colleagues—in a move which would become a theme throughout this last year of his life—had been pressuring him into moderation, pleading that he not condemn the war. Civil Rights leaders in the Urban League and national NAACP condemned him for conflating anti-war demands for civil rights. So did newspapers like The Washington Post and The New York Times. One weakness of the SLCL was that it was a staffed group, not a democratic, membership-based organization. The SCLC therefore relied on contributions from liberal foundations rather than dues-paying members. So when he came out against the war, the SCLC’s budget was cut considerably, creating a crisis in SCLC and the broader Civil Rights Movement. It’s a testament to Dr. King’s commitment that he knew about this risk but made the decision to come out anyway. In one of my favorite descriptions of what movement leadership is and is not, Dr. King told the audience of 500 dissident anti-war unionists later in 1967:

One [Civil Rights leader] spoke to me one day and said, “Now Dr. King, don't you think you're going to have to agree more with the Administration's policy. I understand that your position on Vietnam has hurt the budget of your organization. And many people who respected you in civil rights have lost that respect and don't you think that you're going to have to agree more with the Administration's policy to regain this.” And I had to answer by looking that person into the eye, and say '“I'm sorry sir but you don't know me. I'm not a consensus leader.” I do not determine what is right and wrong by looking at the budget of my organization or by taking a Gallup poll of the majority opinion. Ultimately a genuine leader is not a searcher for consensus but a molder of consensus.

A molder he was. In a continuation of his long-standing commitment to economic justice, Dr. King would launch the Poor People’s Campaign in the last months of his life. The purpose of the campaign would be to compel Congress to pass an Economic Bill of Rights that would provide subsidized housing, full employment, a living wage, and guaranteed income for the unemployed. His vision was to march to D.C., occupy the city, disrupt business as usual, and even block the roads until these programs were created. In the midst of planning the campaign, on February 12th, 1968, 1,300 Memphis sanitation workers—all all of whom were Black—went on strike. This strike, to Dr. King, embodied the Poor People’s Campaign. It was a labor battle led by Black workers that ignited the city of Memphis into a social movement against the neo-Jim Crow establishment. Dr. King would become rejuvenated by it, try to lead it, and die doing so.

In a speech to the Memphis workers in March of 1968, he signaled the strategic transition of the Civil Rights Movement:

With Selma and the voting rights bill one era of our struggle came to a close and a new era came into being. Now our struggle is for genuine equality, which means economic equality. For we know that it isn’t enough to integrate lunch counters. What does it profit a man to be able to eat at an integrated lunch counter if he doesn’t earn enough money to buy a hamburger and a cup of coffee?

Then in this speech Dr. King did something that no modern Civil Rights leader had done. He called on Memphis labor to escalate its struggle using labor’s sharpest weapon:

In a few days you ought to get together and just have a general work stoppage in the city of Memphis.”

The audience of 17,000 strikers and supporters applauded, shouted, and celebrated. He would be the first, and maybe only, civil rights leader to call on the working class to pursue what perhaps he saw as the highest form of non-violent civil disobedience: a general strike.

Although a general strike never materialized, the fact that Dr. King raised the demand, and that it was so enthusiastically welcomed, signaled that a shift had occurred in the Civil Rights Movement. There was potential, yet the nationwide forces to realize it were absent. Dr. King left Memphis the following day to continue recruiting and raising funds for the Poor People’s Campaign. But it was a failure. No major labor leaders or Black ministers responded to King’s invitation to join the campaign. Of course, Dr. King was proposing a radical departure from the mainstream strategy: calling on ordinary workers to see the link between domestic poverty and Vietnam, to oppose Democratic leaders, and to organize themselves to disrupt the system in workplaces and in the streets. In the Cold War era, labor leaders had relied on cooperation and backroom dealing, rather than rank-and-file confrontation, to deliver the goods. It was then as it is now a strategy that straightjackets the labor movement.

King returned to Memphis in April. As he was running a fever, he delivered an electrifying speech improvised (unusual for him) over the sounds of thunder rumbling, lightning cracking, and winds gusting outside Mason Temple. He stressed that unity and solidarity were universal tactics: “when the slaves get together, that’s the beginning of getting out of slavery.” He told strike supporters that “you may not be on strike, but either we go up together or we go down together.”

At the end of what was his last speech, given the day before his assassination, Dr. King had reassured the crowd that he had gone to the mountaintop. Invoking the story of Moses, he said God had allowed him to see the promised land. He assured the audience that the liberation he envisioned was possible. Prophetically, tragically, he said he may not get to see it, but “we as a people will get to the promised land.” Dr. King had suffered extreme depression and exhaustion during the last years of his life, no doubt because of the movement’s decline by Cold War liberalism. Which is why it’s all the more moving that in his last words to the crowd he said: “And so I'm happy, tonight. I'm not worried about anything. I'm not fearing any man! Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord!”

Just like in the story of Moses, today we still wander the desert. Pandemic, war, economic crisis, gender and racial violence, and climate change have imbued many with a sense of directionlessness and despair. But in Dr. King’s life, he reminded many that when it seemed impossible to win legal protections for labor, ordinary workers made it happen in their rebellion in the 1930s. The impossible happened again when Jim Crow was dismantled, often under the leadership of a generation of Black workers who had been schooled in labor struggle.

The best way to honor Dr. King’s legacy is to embrace his radicalism, his emphasis on solidarity, and his tactics of civil disobedience and mass action. To dream the impossible once more, to demand it relentlessly. Unions, with their resources and structural power, have an extra responsibility to this task, for “The cause of labor is the hope of the world.”